It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there’s no knowing where you might be swept off to.

J.R.R. Tolkien

The Differences Between Drugs

Not all drugs are created equal. Some are more harmful, or indeed more beneficial, than others. The more harmful ones are stimulants such as (meth-)amphetamine, cocaine, and mephedrone, and depressants such as alcohol, GHB, the benzodiazepines and opiates, like heroin. They tend to cause the most problems, not just for users but for the different contexts in which users exist. They are addictive, destructive in terms of the health of the user, and disruptive to their surroundings.

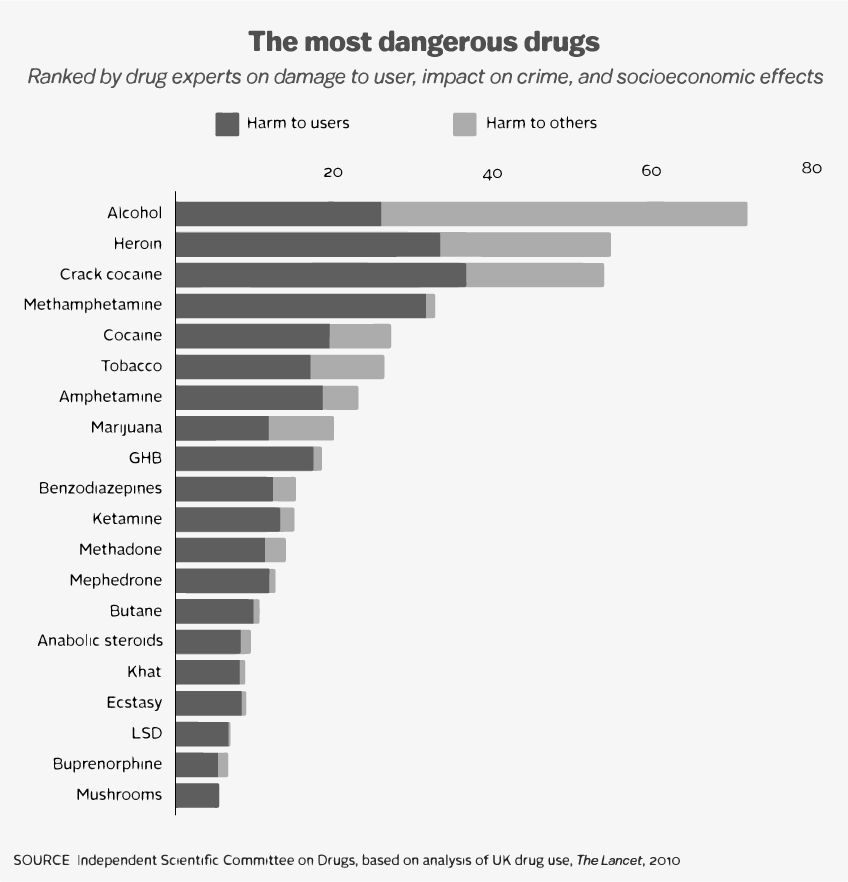

The large class of psychedelic agents are not considered to be harmful, as they are thought to be non-addictive, not bad for the user’s physical health, nor disruptive to their surroundings. The graphic above displays the harmful dimensions of several frequently abused drugs in the UK in the 2000s, as rated by a conclave of professionals in the addiction and public health fields. It is clear that psychedelic substances such as LSD and mushrooms feature all the way at the bottom of the range. Apart from the odd suicide, there has not been a single confirmed fatality due to LSD, despite 70 years of steady (recreational) use. Similar things can be said for psilocybin containing psychedelic mushrooms.

Ecstacy (or MDMA) is not quite a psychedelic but a related substance, sharing some of the same characteristics. MDMA is first and foremost an empathogen, causing users to feel highly connected to others. It is also structurally an amphetamine, which explains its energetic profile and popularity in the dance music scene over the past three decades. Finally, to be complete regarding the bottom section of the graphic, buprenorphine, like methadone, is not a mind-altering chemical but an opioid agent that is applied to wean addicts off stronger opiates, like heroin and fentanyl.

Of course, this discussion does not take into account the beneficial effects of these drugs. Even the most damaging drugs have some, otherwise why would anyone use them? Stimulants provide a boost of energy, which can be experienced as a boost in self-confidence as well. Alcohol and GHB lower a person’s inhibitions, making social interaction more smooth and pleasant. Opiates such as heroin are good at removing the experience of any kind of pain, be it mental, physical or emotional. The result is a general and (initially) long-lasting experience of euphoria.

Psychedelics, too, offer some of these things, sometimes. Their appeal, however, lies more in the altered experience they afford users. You tend to experience yourself, the world, and yourself in that world differently, often incredibly so, while on the drug. This can be frightening on many levels, which naturally limits the circle of people who seriously contemplate taking psychedelics. But it opens up new possibilities as well, such as those for deep insights into one’s mental and emotional processes, and for adventure into far-flung realms of consciousness that are generally only visited by mystics (and lunatics).

The so-called classical psychedelics can be subdivided into two categories: those that work on the brain’s serotonin system, and those that work primarily on the dopamine system. The serotonergic psychedelics are based around a tryptamine chemical structure, which resembles the serotonin neurotransmitter. Psilocybin, DMT, and many of the recently available research chemicals that end in “T” (for tryptamine) fall into this category.

The dopaminergic psychedelics structurally resemble amphetamines, and generally provide a little more energy than the serotonergic ones, although there are many exceptions to this rule. Mescaline, 2C-x, MDA, and many other current psychedelics are included in this family.

A user may or may not be able to tell the difference between a drug from one family over another, so as far as effects are concerned, the subdivision may matter less than you might think. The lysergamides, such as LSD, appear to work on both systems. Finally, there are other substances that have psychedelic effects and that can’t be classified within these two systems, such as salvia divinorum, and the amanita muscaria mushroom.

Most psychedelics alter cognitive processes in some fashion, leading to:

- Visual distortions that can be seen with eyes open or closed,

- Auditory distortions, where one can hear voices, and music can take on a highly meaningful aspect, and

- Cognitive distortions, where concepts, such as relationships, time or space are perceived radically different from how they are otherwise.

Below is a short exposition of individual differences between some well-known psychedelic substances. As the experience is generally quite personal, we will only compare the energetic profile, duration, presence of nausea, and dosage considerations.

Magic Mushrooms

There are well over a hundred different species of mushrooms that contain the psilocybin alkaloid and its analogues. The active ingredient changes into psilocin in the body. Structurally similar to the neurotransmitter serotonin, psilocin and its ilk work directly on a number of specific serotonin receptors in the brain, modifying the way sensory data, thoughts and physical sensations are experienced.

Energy profile: relaxed, stoning

Duration: 3-6 hours

Nausea: ★★★★☆

Dosage: varies per variety. Generally 1 gram of dried mushroom product yields a mild trip. People have of course taken much more than that, with 10 grams or more considered quite heroic but not uncommon. 100mg constitutes the standard microdose. For “wet” mushroom weights, multiply dosages by ten.

LSD

First synthesized in 1938, LSD has taken the world of academe, psychiatry, and the arts by storm. LSD also works on the serotonin system, but has a more broad effect throughout the brain.

Energy profile: energized, stimulated

Duration: 6-12 hours

Nausea: ★☆☆☆☆

Dosage: LSD is one of the most potent substances known to science, with 100 micrograms yielding a mild trip. As with mushrooms, people have taken far greater doses—science has no established lethal dose for LSD in humans. 10 micrograms is the standard microdose.

Peyote / San Pedro (Mescaline)

Native to the Americas, mescaline-containing cacti have been used ceremonially for hundreds of years, at least. Like most classical psychedelics, mescaline works on the brain’s serotonin system to produce open and closed eye visuals, auditory distortions, and a modification of a person’s usual cognitive processes.

Energy profile: energized

Duration: 10-14 hours

Nausea: ★★★★☆

Dosage: 30-350 mg dried peyote buttons // 50-700mg mescaline

Ayahuasca

Mixture of at least two Amazonian plants that leads to powerful healing experiences. May contain other plants, such as the deleriant (and potentially toxic) daturas, so caution is advised. Often consumed in shamanic ceremonies, together with other voyagers, and led by a shaman.

Energy profile: relaxed, stoning

Duration: 4-8 hours

Nausea: ★★★★★

Dosage: depends on the potency of the brew

Iboga

A Congolese shrub that is used for initiation and divination in its traditional Bwiti context. Adapted in the West to be used for recovery from addiction. It is one of the few substances in this class that has proven potentially harmful, due to possible heart toxicity and vascular embolism.

Energy profile: varies

Duration: 6-30+ hours

Nausea: ★★★☆☆

Dosage: 10-20 mg/kg of bodyweight

The Risks Involved

The fact that psychedelics are overall not very harmful and possess some beneficial characteristics does not imply that any of these drugs are benign. They aren’t. Disregarding tolerance for the moment, the immediate effects of all of these drugs are quite strong, and may impair a user’s normal functioning to a much higher degree than a typical dose of more current recreational drugs such as caffeine or nicotine.

Consider going on vacation, which is generally a more risky decision than staying safely at home. The risk may be slight, or it may be large. Travel to Denmark, and you will likely have a good time, unless you are easily ruffled by the odd impolite waiter. Then again, you might get your wallet stolen.

Travel to Somalia, and you might get kidnapped and held for ransom. Then again, nothing out of the ordinary may happen, you meet only friendly, welcoming people, and you end up wondering what all the Foreign Office fuss was about. Just as traveling the world is neither implicitly harmful or benign, in most cases ingesting any psychedelic drug is not either. Just like taking a vacation, however, it does imply taking a certain risk.

The above graph can be seen as an actuarial statement about the risks inherent in engaging in certain drug use. Taking cocaine does not mean that you will end up addicted, stealing from and assaulting others, but taking cocaine is inherently more risky than not taking it. In the same way, psychedelic drugs have a certain risk profile that should not be overlooked.

Risks Flowing from the Legal Status of Psychedelics

Let’s start at the most general level. Barring a number of local exceptions, psychedelics are illegal. They have been illegal for decades, and it’s likely to remain so, recent efforts at decriminalization notwithstanding. One might agree or disagree with the tenets of this prohibition, according to one’s political proclivities. There are valid arguments on both sides of the discussion, and I personally hold nuanced views on the issue, but that is not the topic of this article.

The long-term illegality of drugs has many side effects, such as:

- The criminalization of essentially victimless behavior,

- The lack of oversight as to manufacturing and product quality and the attendant health hazards,

- The lack of knowledge on the part of authorities how to intelligently and compassionately deal with a user’s adverse experience,

- Inflated prices,

- Extraneous crime that flows from the unregulated nature of the market, and

- Inflated costs to deal with this rise in crime.

Deciding to use psychedelic drugs implies your assent to the particular risks this entails. You might obtain a poisonous product, get caught in the crosshairs of law enforcement, or end up hospitalized in an Emergency Room, instead of in the care of people who know how to successfully guide any unexpected turn of a psychedelic experience.

There is a basic human desire for transcendence of one’s daily circumstances. The illegality of drugs makes a crime of acting on this desire, in a way that does not appear to be working. We could, however, envision a situation where we gently, and intelligently, transition from a top-down paternalistic system of taboos and repression, towards a system where the desire for transcendence is recognized and embedded within a culture of support and care for the individual.

Risks Flowing from the Nature of the Psychedelic Experience

More specifically, psychedelics carry a risk of the altered state being more immersive, frightening or long-lasting than expected or hoped for. Whereas alcohol, opiates, and stimulants have rather predictable effects on the user—which unsurprisingly makes up part of their broad appeal—the effects of psychedelics are notoriously unpredictable. This time you may experience heaven, but next month it may take you to hell, or to some nondescript place in Finland. It is also not uncommon that a psychedelic may affect a user’s faculties three or four times longer than is generally assumed to be normal. In unstable people, psychedelic substances may lead to a further, but usually reversible, breakdown of mental and emotional stability.

Three recent developments are responsible for further exacerbating this risk. The first is the mediagenic message that these substances are being used to effectively treat people with long-term, treatment-resistant depression, alcohol and nicotine addictions, and a variety of life-changing fears. That people who have taken a psychedelic agent are less likely to commit suicide than the average person, and that they are less likely to physically mistreat their significant others.

It’s easy to forget that the research studies mentioned were highly regimented, strongly controlled, and expertly guided by professional therapists. And then it’s easy to assign most if not all of the reported benefit to the chemical agent involved. After all, we have grown into a situation where taking advantage of a little chemical assistance is not just normalized, but expected. Six percent of children in the USA are currently being medicated for ADHD, which means that, starting at around age 6, medical doctors are prescribing them amphetamines. Amphetamine, AKA speed, is number seven on our holy list of damaging substances, although it must be said that apparently there are fewer health hazards associated with their therapeutic use, because the prescribed dosage is commonly much lower than typical doses taken by recreational users.

The second development has to do with the ubiquity of information and the resultant “illusion of knowledge” that quite understandably entices people who might otherwise remain resigned to their fate, to now put all of their hopes into this psychedelic substance. There are many forums on the Reddit platform, for example, that tout glowing experiences by formerly depressed people, newly converted to spreading the psychedelics-are-good-for-everything-gospel. And it’s not far-fetched to assume that, if therapy on its own hasn’t worked for you, and legal pharmaceuticals haven’t, perhaps these long-maligned and maliciously suppressed chemicals might do the trick, and somehow “scare you straight,” even without the therapeutic guidance that appears to be so essential in helping these research subjects.

The third exacerbating development is the increased availability of semi-legal alternatives to the outlawed “classic psychedelics”, that themselves remain quite available despite the global War On Drugs. Few of these newly available substances have been through the rigorous real-world testing the classics have endured, and anyone taking these chemicals is in fact treating their body and mind as if they were a laboratory animal. Authorities are catching up ever quicker to the intrepid entrepreneurs who hawk these euphemistically termed “research chemicals.” Consequently, in a frantic game of whack-a-mole, new psychedelic agents are cropping up on a regular basis. Basically, anyone with some understanding of the online world, and enough motivation to do so, can have many of these substances delivered to their door.

It is my hope that in some future scenario, these substances will no longer be considered dangerous or demonic, and that their use will be an integrated, accepted, and safely regulated way to probe the mysteries of being human.

With that said, it’s imperative to understand that recreational use of these substances, be they legal, semi-legal or illegal, is going on, and is not going away any time soon. It’s important to understand why people do so, and what can be done to help them do so as safely and as insightfully as they can.

Users of psychedelics generally aren’t hard-nosed criminals, but rather hopeful independent thinkers, intrepid explorers, or curious revellers. They are on the whole capable of making up their own minds, and are willing to take some risks to achieve their goals. These people are not enemies of the state, or would-be revolutionaries, but well-integrated folks who are looking to more fully experience and express the richness of their humanity.

How can things go wrong?

All psychedelics are by their very nature chemical drugs, or cocktails of them. For all the talk about shamanism, entheogens, and plant teachers, the fact of the matter is that you’re taking a chemical substance in order to change your outlook on inner and/or outer reality.

We can wax philosophical about the ultimate knowability of such a reality, and whether under the influence of some chemical we are able to perceive said reality more or less clearly, but that is not essential to the psychedelic experience. Such considerations definitely factor into your mindset when engaging in this practice, just as any outspoken shamanic ceremony will factor into both set and setting, but they are both tangential to the psychedelic experience. What is essential is the act of taking the drug.

In other words, without the chemical substance, there would be no experience of any altered state. Which is not to say that altered experience is otherwise impossible, that is clearly not true. Nevertheless, the sudden, forceful and decisive alteration that happens under the auspices of a psychedelic are hard—not impossible, but hard—to reproduce without access to this class of drugs.

It is unlikely that psychedelics add anything to your experience of reality. Rather, psychedelics modify perception and cognition in such a way as to make your experience markedly different from the one you are used to. That can be unsettling, and may on occasion lead to people losing hold of their mental sanity altogether. This is one of the major reasons that planning, preparation, mindset, and setting are so important.

Risk of Psychosis

In the mean, those at risk of psychosis are people whose grip on reality was already tenuous. For them, the psychedelic experience serves as a final push towards a prolonged altered state of consciousness that renders them temporarily unfit to take their place in society. In some cases, people have been institutionalized for years, after just one psychedelic experience. Others have committed suicide while under a psychedelic’s influence, or in its wake.

It may even be that such a destabilizing event happens not on the first, or even the tenth psychedelic experience. In fact, people may consider themselves seasoned psychonauts before the onset of psychedelics-induced psychosis. The factor that most seems to predict the risk a person runs to experience this is their hold on, and relationship to, consensus reality.

Risk of Existential Crisis

People take psychedelic drugs for all sorts of reasons. Sometimes, the inclination is to celebrate a good day or night out with friends, aided by a reality-enhancing agent. At other times, a person might be looking for a way to relax, disengage, or temporarily flee from the demands of a stressful period. A growing number of people have found ultra-low-dose psychedelics useful for experiencing a slight mood lift, an increase in energy, productivity, creativity, and a sense of connection, or a relief from a host of sometimes crippling afflictions.

As mentioned, some people ingest higher doses of a psychedelic to take advantage of its purported therapeutic value. People will trip for the express purpose of getting to the bottom of some underlying ailment, be it physical, emotional or mental. In essence, they start self-medicating with highly powerful chemicals, often without a proper support structure, and not infrequently slightly on a whim. Without a plan, not having a centering practice that can balance the crazy stuff that may surface, and lacking the option for adequate outside intervention, they are setting themselves up for a potential “bad trip”. More on bad trips later.

Insights may arrive, but you may not have a clear idea on how to implement them. Or worse, the sheer force of old habits comes roaring back, making it practically impossible for you to carry through on your desire for deliverance. Slowly but inevitably, the memory of the experience greys out, fades ever further into into the rear view mirror, becoming another token example of something you failed at, or something that wasn’t able to help you.

Others intend to travel astral realms, discover the nature of reality itself, or experience what is commonly referred to as ego death. And they very well may. But what did the old adage say? Be careful what you wish for? So you experience the nature of reality, your familiar localized way of viewing yourself and the world fragments into countless little pieces, leaving you free to experience them unmediated by your customary filters of mind.

Let’s assume for argument’s sake that this experience is pleasant – it doesn’t have to be, just youtube 5-MeO-DMT – but let’s assume that it is. Unburdened of egoic restrictions, you’re finally able to perceive this human existence up close and personal for the first time. The experience may be so powerful that you cannot “un-see” it. But, all too soon, your ego is going to reassemble itself and land you back into your old life with nothing but a fading memory of perfect bliss.

So, you’ve had this wonderfully free, blissful and insightful experience, and now you’re back in your old reality, basking in an afterglow that doesn’t last. Without making any changes, the inertia of your old life will draw you back in, but now something is different. You know – not just physically, but experientially – that things could be perceived in a different way, and that you once “had it” and have now lost it. That is a hard burden to bear for most people, and this “vision of heaven,” or more accurately its unescapable absence, will start to subtly bleed through into your everyday existence, coloring many of your interactions, duties, thoughts and actions.

Without the proper integration, an earth-shattering, ego-exploding, mind-bending trip may very well lead to a profound sense of loneliness, depression, and existential ennui. In meditative circles, this kind of experience is referred to by the term “Dark Night of the Soul,” or meditation sickness, which depicts a similar event that can happen to a contemplative practitioner once they get their first glimpse of what the mind is capable of. Calling it an “event” really doesn’t do it justice, as these Dark Night “stages” can sometimes last for months or years, especially when the practitioner in question, or their teacher, doesn’t understand what’s going on.

Life After Ego Death (the book) takes a deep dive into such psychedelic experiences, and carefully charts a way out.

It’s kind of funny when you think about it, if only it wasn’t so sad. A person takes some psychedelic substance with the sheer intention of exploration, almost out of pure curiosity. They experience something great and powerful, but instead of being invigorated by it, or of fueling their curiosity further, they spiral down into some mind-made morass of despair. Be careful what you wish for!

Bad and Good Trips

And then there is the Bad Trip: an experience that somehow terrifies, threatens or otherwise disturbs you, and that can sometimes follow you around like a black cloud, for days, weeks, or months after the experience, making you question your ongoing sanity, and beat yourself up over the stupid decision to take the drug in the first place. Bad trips can happen regardless of motive or setting.

Fear plays a large role in the bad-trip narrative. Fear refers to a threat, sometimes imminent, that never quite materializes. Fear seeks to protect something, and it is worth finding out whether that something truly requires protection. From a high-level viewpoint, fear is both an impediment to, and a catalyst for your deepening understanding of freedom. Bad trips are therefore neither good or bad; it’s what you do with it that makes it anything: the narrative about the experience, which is created partly before, during, and also after the experience completes.

The primary factor that appears to prevent a bad trip is your mindset. More about motive, mindset and setting, as well as other factors, in another article.

Finally, there is the Good Trip, that may impact you so much that something similar happens as in the ego death experience you can’t un-see. There can be the experience of finally firing on all possible cylinders, of finally experiencing what life could be like, if only you could always be like this. And therein of course lies the rub, it wasn’t a naturally occurring experience, but one mediated by chemicals. And time will tell that you appear to be incapable of returning to this flow-like state, at will. Now that you know what you’re capable of, why wouldn’t you want to perform like that all the time?

The frustration of not being able to recreate the flow experience, even when taking the same dose of the same chemical in the same setting, with the same people, with a similar mindset, can drive you up the wall, and put a damper on your overall enjoyment of life, outside of the experience of tripping. This frustration is rooted in a certain fear, as well, and examining that root more closely can help you come to terms with the frustration.

So What Goes Wrong?

Clearly, any motivation to take psychedelics may land you in psychological hot water, due to the very reality-bending nature of these drugs. The reasons that appear to get people in trouble most often are any combination of the following thoughts:

- An overestimation of a psychedelic drug’s therapeutic potential, or a belief that the drug will somehow fix, heal, or liberate you,

- A belief that the psychedelic experience is more real than reality, and

- An inclination, whether strong or subtle, to resist, avoid or run away from something.

Note that none of these thoughts have anything to do with the drug in question. The drug acts as an amplifier for what is already present in the mind of the user, and the memory of the drug experience can act as an anchor to weigh the person down further.

An Overestimation of a Psychedelic Drug’s Therapeutic Potential

It can be scary to take a mind-bending drug of this magnitude. That is perhaps why some people feel that if they have gotten over the fear of the experience sufficiently to bring themselves to actually take the drug, their work is done, and the rest is up to the chemical. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is precisely within the psychedelic drug experience, and also after, that all of your courage and fortitude are needed.

Overestimating the therapeutic potential of a psychedelic drug is what happens when you assume that it is mainly the drug that is responsible for the therapeutic effects reported by science. This is far from the case, and assuming such a distorted view of the therapeutic process is unhelpful. In reality, it is your native self-healing ability that does most of the heavy lifting. This ability should be given the necessary space to work its magic.

The psychedelic plays a part in this, in that it forces your bad habits to recede for a short time, allowing unprocessed stuff to surface and show you what needs to happen for health to return. But, and this is a big but, it can only do this if you’re feeling relatively safe and supported. This is the terrain of set and setting, subjects to which we will return in another article.

Eventually you will see that your bad habits aren’t bad at all, but that they always had your back. They were always working to your advantage, supporting your health and your continuing growth, only from a (much) more contracted understanding of what that was.

Most importantly, if you’re depressed, anxious, or otherwise convinced that your inner or outer environment is unsafe, you’re not going to let go of these bad habits to the degree that is necessary to get the most out of your experience.

It’s not the psychedelic drug that heals you, but the opportunity it affords the well-supported larger sense of you to figure out how you are contributing to your own lack of well-being, and how to change that behavior.

Meanwhile, the psychedelic substance itself should properly be viewed as a guide. It is capable of showing you whatever you desire to see, but only for the duration of its effects (or rather its peak effects), and usually in some contorted, dream-like fashion. It can show you the way in territory you have misplaced the keys to. It is the expectation that the drug will somehow magically heal, free or enlighten you that is truly at fault, and a cause of difficult experiences in general. Healing, working towards more freedom or enlightenment, is the responsibility of the tripper, after the voyage has been integrated and well-understood. Only then does the actual work begin.

If you think about it, no drug has the capacity to heal anything. Even antidotes don’t actually heal you—they bolster the body’s own immune system, allowing it to better fight whatever infection is making you ill. All drugs, whether legal or illegal, can do in terms of healing is to control symptoms of some underlying malfunction or illness. That is what is happening with psychedelic drugs as well. In a sense, your psychological defence mechanisms are a symptom of the underlying illness of the illusion of separation.

If this is disappointing to you, ask yourself the question: would you really want it any other way? Would you really want it to be possible for a drug to change your entire personality, such as it is? What if it changes something you really like? Or what if the drug is wielded by the wrong person, or at the wrong time, or without your knowledge and permission?

A Belief that the Experience is More Real than Reality

In no way can it be said that the psychedelic experience is more real than your habitual perception of reality. The drug can show you another reality, one perhaps where your standard defence mechanisms are temporarily silenced, and where you’re experiencing how it feels to be free from fear, free from self-made suffering, or free from selfing altogether.

The resulting experience is just as real as the way you habitually experience the world, and it is something that is available to you in every moment, if you can find your way back there. This is what mystics have been talking about for millennia, and some of the paths they have taught are effective and attainable for the average person. Placing the psychedelic experience on a pedestal to admire from afar only serves to create a large distance between the you-in-bondage and the free you. I’ll let you guess where that gets you.

An Inclination, whether Strong or Subtle, to Resist or Avoid Something

The tendency to resist, avoid or run away from parts of your experience is quite understandable. It is part of our biological programming, rewarding us to approach pleasure while avoiding pain. Humans are complex biological creatures, and so we have devised many elaborate versions of this basic approach-avoidance paradigm.

Many of the defence mechanisms we talked about earlier can be seen as ways of resisting or avoiding what you at one point in your development have characterized as pain. If the absence of these defence mechanisms amounts to the experience of freedom, perhaps it is worth investigating what happens if you experiment with letting these tendencies go for a while.

More to the point for our discussion here is that the psychedelic drug can only do its job to the extent that you surrender to its power. Fighting the psychedelic experience sets you up for an incomplete experience that is not able to provide you with the lessons that you might have hoped for. But I suppose then that’s the lesson: that holding on for dear life and fighting the experience is not the optimal way to approach a psychedelic experience, or to live your life. Properly integrated, taking the experience to begin a process of learning to let go of control can be a pivotal point for you.

An important point to make here is that all of the aforementioned difficult experiences harbor the chance to grow and learn, but it needs to be recognized as such. This attitude is foundational. It’s not quite “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,” but more like “life is your teacher, and it’s your job to figure out what the lesson is today.”

1 comment